R. G. Campbell

The Fryer Library at the University of Queensland holds the Louise Campbell Collection (UQLFL120), 9 boxes of material relating to Louise Campbell’s life that also includes several objects related to her husband Ron Campbell’s career as an editor of the Australian Journal from 1926-1955. This material includes a typescript that provides a fragmented autobiographical account of Campbell’s life as an editor, nominally titled ‘An Editor Regrets’, and a typescript of an anthology of Australian Journal short stories that was never published, ‘The Australian Journal Story Book’. The Fryer material captures Campbell in a reflective mood as he looked back on his career as an editor with an opportunity to choose those stories that he thought were the best the Australian Journal had published. Bound with sheets torn from the Australian Journal, a letter to Beatrice Davis of Angus and Robertson indicates the proposed destination for the anthology. But no record of Davis’s response has been found. ‘The Australian Journal Story Book’ exists only as a plan proposed by a prominent figure in the print culture of his time. My Fryer Library Fellowship project will position this cultural artefact within the literary and print culture of its time in order to explore the conditions for freelance story writers and consider the inclusion and exclusion of these writers in Australia’s literary history.

The Australian Journal was one of Australia’s (and the world’s) longest-lived magazines, running continuously from 1865-1961. Several studies have examined the magazine in the nineteenth century, but little is known about the sixty-one years of its existence in the twentieth century. Ron Campbell was editor of the Australian Journal from 1926 until 1955, presiding over a period in which the magazine maintained a significant circulation and published the work of many Australian writers. Campbell’s tenure ended in 1955 when the magazine was sold by A. H. Massina & Co to Southdown Press. The Australian Journal published many unknown writers, but it also welcomed some of Australia’s best-known writers into its pages. The ‘Australian Journal Story Book’ includes stories from Marcus Clarke, ‘Waif Wander’, J. P. McKinney, Roy Bridges, J. H. M. Abbott, Osmar E. White, Xavier Herbert, Vance Palmer, Gavin Casey, Margaret Fane, Hilary Lofting, Robert S. Close, Jon Cleary and several other writers forgotten by recent literary history.

Australian Journal, January 1938.

Often seen by critics and literary historians as a publisher of ‘pot-boilers’ and maudlin romance, the Australian Journal of the twentieth century has attracted little attention except for its role as publisher of fiction from Xavier Herbert and Vance Palmer. But, as the list of writers above shows, the Australian Journal provided a space for many Australian writers to hone their skills and to earn a living in a marketplace where such opportunities were few and far between. The importance of the Australian Journal to emerging writers is seen in several dedications to Campbell in novels from such authors as Robert S. Close and S. H. Courtier. With a recommendation from Campbell and a selection of Australian Journal stories, Jon Cleary first broke into the American short story market in the mid-1940s, initiating his forty-year career as a trans-national novelist with a lucrative association with the Saturday Evening Post. Perhaps unexpectedly, several Australian Journal stories were selected in the annual Coast to Coast anthologies during the 1940s, a publication that was known for choosing the best writing of the year. Because of this, R. G. Campbell and his Australian Journal deserve more attention than they have so far received.

This project will build on my research on trans-national magazine culture, particularly the work on trans-national writers such as Louis Kaye and Vance Palmer. This project will closely examine Campbell’s biography and his selection of stories in conjunction with an analysis of the fiction published in the Australian Journal during Campbell’s editorship. Campbell’s editorial voice will be further explored by scrutinising his ‘In Passing’ column, which ran in the Australian Journal throughout his editorship. This study will demonstrate the significance of the Australian Journal in the twentieth century by positioning it in the print culture of its time. This will place more emphasis on the magazine as a publisher of short fiction and show that it had a greater (or different) significance to Australian writing and writers than most literary histories suggest.

The period under scrutiny roughly coincides with the years 1930-1950, the decades that Bruce Bennett, in his Australian Short Fiction, would say reverberated with ‘Local Loyalties and Modernist Impulses’. Bennett points out that the ‘1930s saw a boom in short story writing in Australian magazines and newspapers which was accompanied by rising expectations of the genre as an art form.’ Vance Palmer, one of Campbell’s most prominent writers (in Australian Journal pages under his own name or as the more disposable ‘Rann Daly’), was also one of the most vocal advocates for the short story as a form, but evolved from someone who warned that fiction should not move ‘too far from the bazaar and the market-place’ to become more modernist by moving towards ‘more delicate and subtle psychological exploration’ in his short stories. As I have shown elsewhere, Vance Palmer straddled these two worlds of ephemeral commercial fiction and more enduring literary fiction with ease but not without complaint for having to do so.

But back in the archive, Ron Campbell’s autobiographical fragments tell us something about the man and his career as editor of a popular magazine. The following paragraphs draw directly on Campbell’s ‘An Editor Regrets’ typescript and his description of the Australian Journal in The First Ninety Years: The Printing House of Massina, Mebourne, 1859-1949.

In the early 1920s Campbell was a school teacher with an aspiration to write the great Australian novel. But with a journalist uncle he was well aware of the precarious nature of the freelance writer and so began to write stories that had a greater chance of selling. He took some of these to the Australian Journal offices and an impressed Stanley Massina (Mr Stan) sent him away to try his hand at a 10,000 word detective story. If he could return with a suitable product in an efficient time, the languishing ‘Detective Album’ was his for the taking. He did so and got the job, continuing to work as a teacher and writer from 1922-1926.

Then, when the frequently absent 81-year-old Mr Adcock finally retired as editor of the Australian Journal in 1926 (a tenure that stretched back deep into the nineteenth century), Campbell was offered the position, one that he would occupy for the next thirty years. Under Mr Adcock, the Australian Journal relied heavily on syndicated fiction and paid scant attention to Australian writers of any merit. Under Campbell’s editorship, the Australian Journal would become a haven for Australian writing (of a particular type), supporting many Australian writers with regular payments that other magazines could not match. As Campbell himself put it in The First Ninety Years, ‘from a compilation of stories by amateurs or semi-amateurs the magazine developed into a vehicle for almost every Australian whose work was worth reading.’ Circulation rose from modest sales of 30,000 in 1926, maintained a healthy 54,000 during the depression, and reached a peak of 120,000 in 1945. The Australian Journal took its brand of short stories to a wide readership within Australia and across the world.

As Russell McDougall’s work on Xavier Herbert’s short stories shows, most of Ron Campbell’s Australian Journal fiction was presented ‘through the lens of popular fiction’. In Campbell’s own words (to Xavier Herbert), Australian Journal readers were ‘mainly women, with limited literary tastes and expectations … Romance was de rigeur. Realism was barred.’ It’s also worth getting Herbert’s opinion out in the open. He loved the attention Australian Journal readers brought to him, but that didn’t stop him from referring to them as ‘mutton-heads’. In a letter to P. R. Stephensen during the 1930s, he wrote:

The best magazine in Aust. today is the Australian Journal. It is in fact the Real Magazine. And it is a very comfortable concern, eighty years old and getting older and more comfortable. Doubtless you know nothing about it. Few literate people do. It is a journal for illiterates. It could claim the patronage of literates too if properly run. The editor has often told me not to waste my time on what he calls Pretty Writing, because the class of reader he caters for realises nothing but plot. (Xavier Herbert, Letters, p. 12-13)

In his autobiographical fragments, Campbell points the finger at ‘academics and highbrows’ as the ones with such opinions, opinions that suggest that the Australian Journal ‘was a trivial publication, suitable only for the less knowledgeable type of housewife.’ Nevertheless, those writers Campbell singled out for special attention in his anthology and elsewhere had a stronger reputation in their day than they do now, and many of them were seen as experts in the field of story-writing, as this advertisement for a story-writing course shows.

Advertisement from Australian Writers and Artists’ Market, Including New Zealand: A Practical Selling Guide for the Freelance, 1946

Advertisements such as these suggest the importance of seeing these figures as freelance writers taking advantage of any opportunity available to make a living from their pen or their portable typewriter. For this period between 1926-1955 in Australia there were limited options to get published in the first place and even further limitations if you expected to get paid. It’s worth stressing that the Australian Journal was probably one of the highest paying outlets in Australia and maintained this reputation throughout the depression when others faltered.

During the 1940s, the Australian Journal often advertised Bernard Cronin’s Story Writing Course.

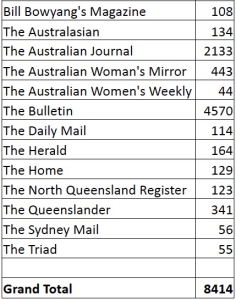

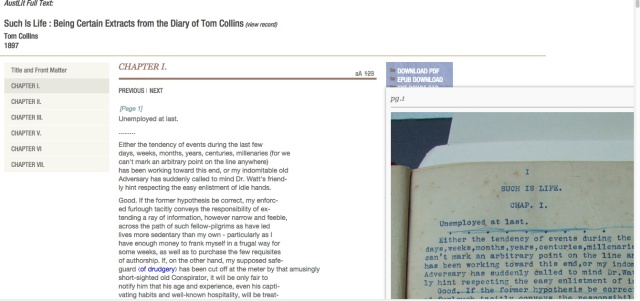

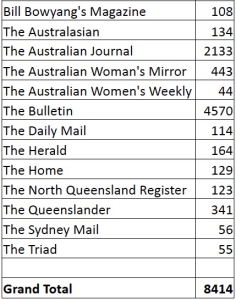

Bibliographical data extracted from AustLit allows us to look at the field from a broad perspective. A search (in July 2016) for short stories published in periodicals provides some interim data (interim because not all Australian Journal issues have been indexed, but, nevertheless, it is still the most comprehensive bibliography available). As the tables below show, the Australian Journal is positioned beneath the Bulletin as the main publisher of short stories during Campbell’s editorship, but far above other competitors. The second table below gives us an idea of the the number of stories accepted from Campbell’s preferred writers, as well as others of interest that some have suggested deserve more attention than accepted literary history provides. (I’m thinking here, particularly, of Myra Morris, Georgia Rivers, and Jean Campbell), but all will be worth a reevaluation within the period in which they were most active as freelance short story writers.

Top 13 Short Story Publishers, 1926-1955. (Source, AustLit, July 2016)

R. G. Campbell’s favoured writers were among the most prolific contributors to the Australian Journal, 1926-1955.

I have shown elsewhere how Vance Palmer’s commercial and literary fiction have significant inter-textual relationships, and there is no doubt that other connections will be found between the ephemeral Australian Journal short stories of others and the fiction that built their reputation. For instance, Xavier Herbert’s ‘Seven Emus’, published in the Australian Journal in 1942 was significantly revised for it’s 1959 book publication. Other authors on the list might also surprise as J. P. McKinney’s Australian Journal short stories have done for a few seasoned bibliographers. Unknown and understudied, McKinney’s ‘According to Noonan’ series places him firmly within the tradition of Steele Rudd’s comic portrayal of life in the Queensland back blocks. Better known for his philosophical writing and a prize-winning war novel, McKinney is revealed here as someone who made a living with commercial fiction in the 1920s and 1930s, before turning his hand to radio serials based on characters from his Noonan series. Writers like McKinney are not writing in isolation, producing works of art disconnected from the culture that surrounds them. Their relationships with editors, publishers, and other writers are worth considering.

An illustration that headed many of McKinney’s Noonan stories.

The passive and active position-taking or position-making within Australia’s literary and print culture draws attention to the benefits of employing Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of the ‘cultural field’. The relationships that form between writers, publishers, critics and readers can tell us a lot about the period of time in which these individuals and institutions were active, and so this project will exploit that as much as possible in order to provide the broadest account of the story-writing freelance in the middle decades of the twentieth century. Closer examination of the profiles and relationships that emerge from the archive for each writer will contribute to a fuller consideration of ‘The Australian Journal Story Book’ as a product of its time. The questions that arise will require some time in other archives to compile the evidence needed to support the biography and bibliography that will better accommodate these freelance writers within literary history. Evidence from the archive will be complemented by distant views of literary and print culture through tables, graphs and network visualisations such as those included in this post.

Network visualisation showing relationships between short story writers and the top 13 publishers. The Bulletin is the central node on the right. The Australian Journal on the left. Many of Campbell’s ‘experts’ are situated in the middle of the visualisation, indicated by the small green nodes and connecting lines.

With the help of the Fryer Library and UQ’s digitisation program, there is huge potential to ‘liberate the archive’ through thoughtful digitisation that supports the biography and bibliography of this project, drawing attention to Ron Campbell’s autobiographical fragments and his unpublished anthology, and demonstrating the value of these items as significant cultural objects that demand further scrutiny.