Joseph Furphy in the State Library of Victoria

‘Ignorance-shifting’ was, for Joseph Furphy, ‘always a labour of love’, to which he turned with enthusiasm whenever he had ‘paid the Adamic penalty’ of labouring for his daily bread. From boyhood, when he learnt passages of the Bible and Shakespeare even before going to school, to old age, when he confessed to his mother – that same mother who had taught him to read – that he was ‘the slave of the printed book’, Furphy sought knowledge. ‘My idea of dissipation’, he once told the young bushman and would be writer, Cecil Winter, ‘is to revel in some new volume of one of my favourite sciences – Ethnology or Astronomy’. A man who earned a living by manual work, Furphy could see no reason why ’the manual worker should be rude and illiterate; shut out from his rightful heirship of the ages’.

There were few books in the hut on the Ryrie station in the Yarra Valley where Joseph Furphy was born on 26 September 1843. His parents – embodiments of the classic Protestant virtues – had come to ‘the working-man’s paradise’ from Northern Ireland where their families were tenant farmers. To their children they passed on a strict moral sense, a belief in hard work, and, most important of all for the future writer, a respect for learning and a love of literature. Eventually they were to realise the dream of owning their own land, taking up a selection near Corop which is still farmed by their descendants. Joseph, who spent much of his youth ‘dodging out of farm work’, could foresee no other occupation for himself, and along with his parents and other family members he selected land in the late 1860s.

"He earned a precarious living with a team of bullocks, first in the Corop district and then, from 1880 to 1883, in the Riverina."

Writing was for Joseph Furphy – and for other members of the family – a form of self-expression to be enjoyed when there was leisure. As a boy he had amused himself by writing verse parody, ‘Childe Booth’s Pilgrimage’, in which he showed off his knowledge of English poetry. He had a brief moment of fame shortly after his marriage in 1867, when he won a local competition for a poem of the death of Lincoln.

But a struggling selector with a young family had little time for reading and less for writing. And when in 1877 Furphy could not meet his debts and lost his land, things were no easier. For the next six years he earned a precarious living with a team of bullocks, first in the Corop district and then, from 1880 to 1883, in the Riverina.

The years in the Riverina, when he tramped beside his team, taking supplies from the railhead at Hay out to the sheep and cattle stations and returning with wool, left an indelible mark on him. Often alone for days on end, separated from his wife and children back in Hay, he carried pocket editions of Shakespeare for reading by camp fire at night. Meetings with other bullockies and travellers on the plains were occasions for the exchange of ideas as well as news. A shearer who camped with him one night remembered him as ‘the most learned bushman that I have ever met, a real bushman’; but went on to reflect that ‘Joseph Furphy was of us, but not one of us’.

‘the most learned bushman that I have ever met, a real bushman’

There was plenty of time for reflection on metaphysical questions, and on more immediate social and political questions. For the first time in his life he was led to examine critically the values that he had been taught from childhood.

Such considerations were secondary, however, to the business of earning a living. Although he prospered for a time, and had two teams, he was always aware how vulnerable he and the other teamsters were to circumstances over which no man has any control. In the drought of 1883 his worst fears were realized when his bullocks perished, and consequently he lost his means of livelihood. With this disaster ended any hopes he may still have had of being independent as were his brothers and sisters.

For Joseph Furphy, his brother’s foundry was a haven. Now, for the first time in his life, he enjoyed the advantages of working regular hours; having paid ’the Adamic penalty’ for eight hours each day, he could turn to his books. At the back of his cottage on the bank of the Goulburn River, he built an unlined lean-to, just big enough for a table and chair, a bookcase, and a stretcher bed. Night after night he was in his ‘sanctum’, reading and writing by the light of a lantern shaded by an old felt hat. His experience of the Riverina made him receptive to the ideas of Socialism that were espoused by some of his fellow-workers in the foundry. The Sydney Bulletin, with its message of “Australia for the Australians’, became his regular reading. He took little part in the affairs of the town, where his brother was a leading citizen. When he ventured out of the sanctum it was most often to the nearby Mechanics’ Institute.

Of the ‘mechanics’ in Shepparton, comparatively few belonged to the Institute, which attracted the bourgeoisie rather than the working man. Furphy was technically a ‘mechanic’, and probably no-one made a greater use of the books it contained that he did. The Mechanics’ Institutes were an important element in colonial culture, but their value seems to have varied from place to place. In Shepparton, as in some other Victorian country towns, the introduction of billiard tables turned the languishing Institute into a flourishing social centre. For Furphy, however, the attraction was books not billiards. When revising Such is life for publication, he found himself ‘so blocked by my own infernal ignorance that he ‘wore a pad’ from his sanctum to the copy of the Encyclopedia Britannica in the Mechanics’.

"her belief in his abilities gave him confidence

to undertake the writing of Such is life."

Such was his hunger for information that he enlisted the help of friends in Melbourne. A fellow-blacksmith, William Cathels, who worked in South Melbourne, was the only man of his acquaintance to whose erudition he acknowledged himself inferior. For Kate Barker, a young schoolteacher whom he had met in the country, he was the unequalled authority; and her belief in his abilities gave him confidence to undertake the writing of Such is life. From time to time she would receive a request to visit the Melbourne Public Library on his behalf to check something which he had read on one of his own rare visits there. No writer ever valued a library more.

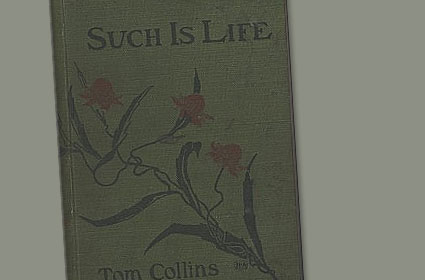

For years he laboured over the book to which he eventually gave the name Such is life. He had no literary acquaintance, and he had published little – only paragraphs and verse in the Bulletin – by the time he was ready to send the bulky manuscript (1,125 pages in his copperplate handwriting) to a publisher. The first reader of the completed work was A.G. Stephens, Literary Editor of the Bulletin, who pronounced it to be ‘fitted to become an Australian classic or semi classic’. It was published by the paper in 1903, shortly before Furphy’s sixtieth birthday. At the end of the following year he moved to Perth, where his sons had established their own foundry, and died there in 1912.

Such is life, which was his major work, is an extraordinary achievement, distilling the thought and experience of a lifetime. Furphy was not the only autodidact in a country town in the colonies to attempt literature – there were other would-be novelists in Shepparton itself – but he was the only one who succeeded in producing a work of enduring worth. Behind the work is Furphy’s experience as a bushman – and as a reader.

"It is a book for readers who are prepared to think."

The knowledge in which Furphy so delighted has, however, proved to be a problem for later generations, who do not share his cultural values. His consciously literary style, with its rich cargo of allusion and punning, his unusual approach to narration, which calls upon the reader to play detective, and the extended digressions by the opinionated and pedantic narrator, do not make for easy reading. It is a book for readers who are prepared to think.

A hundred years ago Furphy was finishing the book into which he put not only his knowledge of life but his hopes for a future Australia. The issues of identity which were so central to that time are once again a focus of public discussion. Such is life offers to contemporary readers an insight into that earlier Australia, as interpreted by a man who observed life with an ironic yet compassionate eye, and thought long and hard about it.